You will never be Manhattan (and shouldn't try to be)

An obsession with New York City, or more specifically Manhattan, is understandable. It’s a very unique city, unlike any other in the world, so it’s not entirely surprising that many cities would like to copy some of its magic. Consequently, you see a lot of articles touting Manhattanization: the Manhattanization of Toronto, the Manhattanization of Seattle, the Manhattanization of London, and on and on. Ignoring how bizarre it is that cities want to lose their own identity and replace it with another, the crux is that you can’t become Manhattan by building generic 21st century glass boxes. The whole character of Manhattan, the buildings that make it special and define its streets, were almost all built before WWII. Pre-war Manhattan, “Gotham” if you will, comprised of industrial mid-rise loft buildings, elegant townhouses, and limestone-clad office and apartment buildings, is the Manhattan everyone falls in love with. That’s the side of the city that draws millions of visitors every year, not the generic modern skyscrapers which look exactly the same as plenty of other modern skyscrapers throughout the world. Manhattan is Manhattan despite all the modern glass towers, not because of them. The frustrating part is that it’s not even that difficult to make a good high-rise. The best skyscrapers of New York’s past, such as the Chrysler, Empire State, Flatiron, and Woolworth Buildings, are deceptively simple in form, relying instead on real windows, natural materials, and impressive cornices rather than the odd forms or blank walls often employed in modern high-rises.

Even New York risks losing a lot of its own appeal if they continue allowing the demolition of historical buildings to make way for generic condo and hotel towers. Bottom line: cities need to stop trying to be Manhattan, because it will never happen with generic architecture. Instead, they should embrace and amplify the aspects which already make their cities unique. For most cities that means preserving and restoring old buildings, and vastly higher design standards for new buildings with a lot less glass and more local, natural materials.

Do we really need towers?

It’s common to see the argument that high-rises are necessary in big cities because of the lack of space. This argument is valid for islands like Manhattan and city-states like Hong Kong or Singapore, but it absolutely does not fly anywhere else in North America, where cities are surrounded by surface parking lots and ultra low density strip malls. Even San Francisco has its fair share of parking lots in close proximity to the downtown. If you have surface parking lots anywhere near your downtown, you do not need to build high-rises.

I believe the whole purpose of urbanism, indeed of a city, is to spread the life-filled, walkable parts over a larger area, not just concentrate it in a small core of individual towers surrounded by a sea of car dependent suburbs. A good example is Toronto, which has a surprising amount of large surface parking lots just a few blocks outside of the downtown core, and yet there are dozens of new condo towers under construction, to the delight of developers. These parking lots are dead zones, making it more difficult to make a coherent high quality urban fabric, a condition further worsened when the city allows high-rises to be built, rather than first spread development onto land which is currently parking lots, one-story buildings, or random brownfield land. Yet you still have architectural pundits in Toronto advocating for upzoning streets of single family homes so that developers can build overlooking towers next door to their homes, as is the case in Yonge-Eglinton. We forget that for most people a home is not just a property, and there are very real emotional connections attached to it. It’s little wonder you get NIMBY movements in such situations. I wouldn’t want a 30+ story tower built next to me either.

If, however, density was introduced incrementally (as had always been the case throughout history), it wouldn’t feel like such an assault on existing residents. For example, by building British style terraced housing on the the existing parking lots, maxing out at 6 stories, with beautiful architecture to match. Imagine, a process whereby a North American city is slowly beautified instead of continually made more ugly by new and bigger towers! These parking lots, in prime locations, represent a once in a generation opportunity to build beautiful new mid-rise neighborhoods so that Torontonians can finally stop saying "Toronto is ugly," as I have heard many times. Surely that should be the aim of the city's leaders?

|

| Large surface parking lots in downtown Toronto. They are a blight on the urban fabric, but are an excellent opportunity to develop beautiful new mid-rise neighborhoods rather than relying on generic glass condo towers. |

The same complaint can be leveled against Indianapolis, near where I grew up. The downtown has its fair share of towers, too, yet it’s surrounded by parking lots, blighted properties, and even completely empty plots of land less than a half mile from Monument Circle, the center of the downtown. By foregoing the towers, the urban fabric of downtown Indy could spread over a larger area, replacing the dead zones with vitality, making it a more pleasant place for everyone, including neighboring communities. Really it boggles the mind, to build towers in the name of density, only to then have parking lots next door which take up more land than the towers themselves! All the more painful to think that many beautiful historical buildings have been sacrificed on the altar of this madness. A twisted sense of corporate ego (with a dash of minimum parking requirements) is the only viable explanation.

|

| Surface parking lots take up entire blocks in downtown Indianapolis, including across the street from the 1888 State Capitol building. In fact, outside of the 8-block downtown core, parking seems to take up more space than actual buildings. This is a serious dereliction of priorities. |

This might be a good time to discuss centralization. The US used to be a lot more decentralized economically, with cities throughout the country, like Cleveland and Buffalo, benefiting from the country’s economic growth. Today, many medium sized cities are suffering, while New York, San Francisco, and Seattle are booming, resulting in insane housing costs. You see the same thing in the UK, where London is disproportionately important to the country, with little happening outside of its influence, resulting in large disparities in housing costs between London and other cities. In Germany, however, you don’t see quite such an extreme, with Berlin, Munich, Hamburg, Köln, Frankfurt, Stuttgart, and dozens of other cities all sharing economic duties in a country with a far smaller population than the US. None of them dominates the economy, partially because the German economy relies on manufacturing rather than financial manipulation. What you find as a result are housing costs much more reasonable and in line with salaries, and you don’t see such huge cost differences between these larger cities and medium sized cities. Therefore many cities benefit from the country’s success, not just a select few. Consequently, high-rises are a rarity in German cities. The strategy of spreading the load doesn’t overwhelm any one city, so they don’t need high-rises to help relieve pressure. The same strategy is seen on the local level. German cities have excellent public transit systems, allowing businesses to be spread throughout the city, not just in a central core, resulting in a large yet gentle, walkable urban fabric, where people eagerly enjoy spending time in. Compare this to the decentralized, suburban model of most North American cities, where almost no one can walk or take public transport to work, but must instead commute great distances to work, for shopping, to school, etc. and where a lot of land is wasted on parking lots or nothing at all. It’s a blah model that results in blah cities that nobody loves.

Setbacks and light

Setbacks have historically been used in buildings to reduce a building’s load, thereby enabling taller structures, with the added benefit that a tower which gets thinner towards the top is more interesting aesthetically. Not long after skyscrapers started to rise (in height and popularity), there was an understandable concern that they would block the sunlight of neighboring streets and buildings. Some cities, like New York, mandated stepped setbacks as a result, the effect of which can easily be seen with buildings like the Empire State Building and the Chrysler Building. In 1961, these setback requirements were eliminated. Consequently, newer skyscrapers in New York and other cities are designed to maximize floor space, at the expense of daylight reaching the street below. More often than not they’re generic bland boxes, and terminate at the top abruptly without anything resembling a roof.

The reason setback requirements were eliminated is easy enough to understand (pressure from developers), but what I can’t understand is why I’ve often seen the argument that blocking the sun isn’t an issue. Do we need the sun less now than we did 100 years ago? My own experience in New York and other cities suggests otherwise. North/south running streets are usually fine, but east/west running streets surrounded by tall buildings are dark and little used, feeling more like big alleys than dignified city streets. It must be even more unpleasant to have a north facing apartment on a street like this, dark at every hour of the day.

Vancouver is often held up as a model city for how to do density, and they get many things right, but the obsession with towers is unfortunate, something made abundantly clear when I recently watched a driving tour of downtown Vancouver. It was a sunny day, but rather than be bathed in light, many of the streets were dark and hidden in shadows from the towers, not helped by the fact that the city's new buildings are not particularly attractive architecturally. You can see the video here.

The shadows cast by tall buildings are a particular problem in winter and early spring, when the sun is low. In places where towers abut a park, the south side of the park often never sees sunlight, like the southern edge of Central Park in New York. In winter, this no-sunlight zone can reach far into the park. In early spring, sunny spots can already be quite warm and pleasant, whereas shady areas are still bitterly cold. This can mean the difference between a park used by residents, and one avoided by residents. To see the effect of shadows in New York, The New York Times created an excellent shadow map. During the winter, most east-west streets are in shadow 100% of the day, as are many north-south streets in areas with a lot of high-rises. This is particularly a problem in colder cities like Toronto and Ottawa, especially during an unusually cold winter like this year. Even on sunny days it's difficult to find refuge from the cold on the sunny side of a street, when there is no sunny side as a result of shadows from high-rises.

|

| The New York Time's shadow map of New York. Dark blue represents areas which never see the sun during the winter. |

The lack of sunlight reaching the street below is a real problem in high-rise cities, not something to simply cast aside as irrelevant. It’s less a problem for the often wealthier residents of the towers themselves who live on the upper levels, but it is a problem for those who live on the lower levels, and those who live close to the high-rises. High-rises are inherently selfish dwellings, rewarding inhabitants with great views… at the expense of those in the streets below.

I dislike the term “access to daylight” that is often used in planning and development circles, as if it was some sort of optional luxury. Before high-rises came along, daylight was just always there, right outside your window! It wasn’t a privilege, or something that needed to be protected. The importance of natural daylight to our mental health is well documented, and just common sense. Reinstating height limits and setback requirements would be a good first step to making high-rise cities more pleasant places to spend time in.

No escape

Unlike other buildings, if a tower is ugly, you’re forced to see it for miles around. You can’t just walk past it or turn a corner to escape it. It’s visible throughout the city and far into the countryside. This makes the low quality of design of most tall buildings all the more despairing, and the need for improved design standards all the more important.

Buildings kill billions of birds

Every year, billions (yes, billions!) of birds are killed when they fly into buildings (by some estimates, 750 million in the US alone). At night, all-glass buildings are difficult to see with their disorientating reflections, and birds just don’t expect them because they’re not programmed into their instinctive flight patterns. The problem is particularly stark because many cities are built next to bodies of water along many species’ migratory paths. To anyone with empathy, this fact alone should be a black mark against high-rises, and an immediate moratorium should be imposed on all high-rise approvals until an effective solution is developed (if such a solution is even possible). Until such time, as a society we are essentially saying that our fetish for tall buildings takes precedence over the lives of scores of other living beings.

High-rises are not environmentally friendly

Contrary to what some believe, high-rises are not energy efficient. They are built in the same manner the world over, with no accommodations made for the local climate. Whether London, Dubai, or Bangkok, the same glass curtain walls are used. The large expanses of glass let in a lot of heat in the summer, and cold in the winter, requiring powerful air conditioners and heaters to regulate the temperature. Furthermore, almost all skyscrapers have inoperable windows (for safety reasons), completely isolating inhabitants from the natural environment. Instead, they rely on power-hungry mechanical ventilation.

Another rarely discussed issue is the tremendous material requirements of towers, exponentially more per square foot of floor space than low-rise and mid-rise buildings. They require very robust foundations made from huge amounts of concrete, often with dozens of large piles going deep underground. The most egregious use of materials, however, is a result of the concrete core. You see, towers are not actually that efficient space-wise. A very large portion of the floor plate is not usable, as it’s occupied by a concrete core which contains dozens of elevators, emergency stairwells, services, ducts, etc. In skyscrapers which taper towards the top, the core can even take up more space than the habitable rooms. Tall buildings also require powerful pumps to deliver water to the upper levels.

|

| Most skyscrapers, such as 1 WTC shown here, have less usable floor space than that occupied by the concrete core. |

In stark contrast, traditional mid-rise buildings require none of that, just your usual stairs and a few elevators, and systems and services which differ little from standard domestic standards. They can be built from a variety of materials, even wood, since they don’t have to support such extreme loads. They are also infinitely more adaptable, and can easily be converted between residential or commercial use, depending on cultural or economic swings.

What’s the alternative?

The answer can be found in the same place as most answers to present-day urban design dilemmas: in the past. That was a time before our age of arrogance and ignorance, when architects and designers built upon the lessons of their ancestors, a learning cycle spanning thousands of years. That answer is to eliminate minimum parking requirements (as some cities are finally doing) and build mid-rise buildings, historically maxing out at around 8 stories, which is plenty for a dense yet still livable city. Such maximum heights are seen throughout Europe and in American buildings from the 19th century, a height mandated not so much by construction technology, but by the presumed limit someone would want to climb the stairs, this being before the invention of the elevator. Acclaimed urbanist Jan Gehl recommends an even more constrained limit of 5 stories, as he says this is a height from which it is still possible to participate with the life of the street and recognize a human face. The higher you go, the more isolated you are from the city. A tower is a world unto itself, a vertical gated community separate from the street below. This is a psychophysiological limitation, not something that can be fixed by throwing more technology at the "problem". To be part of your street, you have to live in it, not up several dozen meters above it.

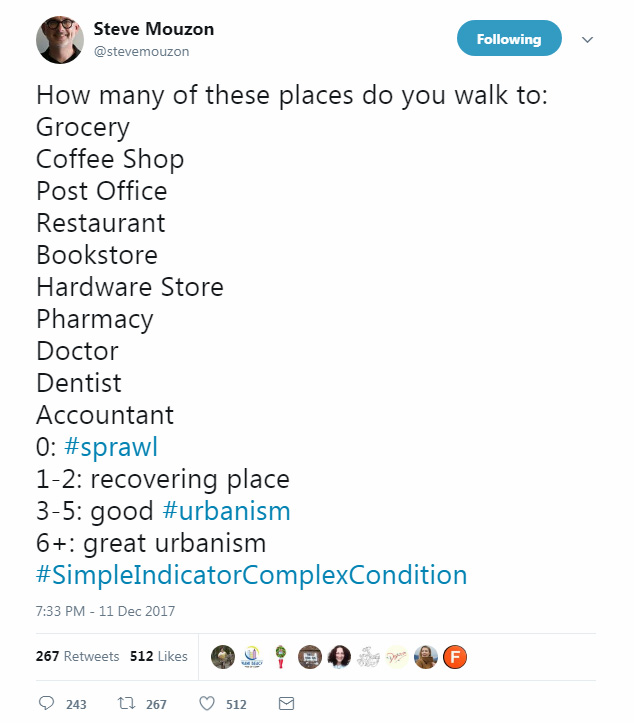

It needs to be stressed that most North American and European cities really don’t need towers. It's certainly not due to density, as the densest neighborhoods in Europe are in Paris and Barcelona, in exclusively mid-rise areas. These are areas where it's possible, even desirable, to live a walkable life without ever needing a car or even public transport for most daily tasks. Cities like London and Oslo show that a walkable city is possible with significantly lower levels of density, and it doesn't require any sacrifices. Low-rise American cities in the 19th century were walkable, too, long before cars or high-rises arrived. It's a complete myth that you need high-rises to support walkable densities, and for many people such as myself, the overbearing nature and lack of sun caused by high-rises makes walking less enjoyable.

In many ways, skyscrapers represent our increasingly artificial world, a physical manifestation of societal and corporate detachment and inequality. Like distant watchtowers of a foreign enemy, they make a mockery of the world below, oblivious of their damage. They are symbols of the abuse of technological progress and environmental recklessness, and party to a system of urban development where land is disposable, nothing more than a resource to be exploited, and beauty not even a consideration.

Which is why the answer is the same as it has always been, and as it always will be: build human-scaled cities full of beautiful buildings that delight the senses in all seasons of the year and that work with the local climate. Build in such a way as to enhance the urban fabric, not sabotage it, and build buildings that people will love and that will last, because that's the only way for true sustainability. Build not for investors, but for the people who will live and work and pass by the building every day. It's really not difficult.

Sources: